Sarah McEneaney’s painting technique is deceptively simple, reminiscent almost of folk art in its deliberate flatness, bright colours, elevated viewpoint, and attention to surface detail. The works of Grandma Moses come to mind, particularly in McEneaney’s bird’s-eye view renderings of the elevated Rail Park in Philadelphia’s Callowhill neighbourhood, from which this show takes its title. Shadow and modelling as a means of creating depth are deliberately eschewed in favour of a more tableau-esque presentation where the foreground and background are treated with the same amount of definition, laid out along occasionally visible orthogonal lines to suggest one- or two-point perspective.

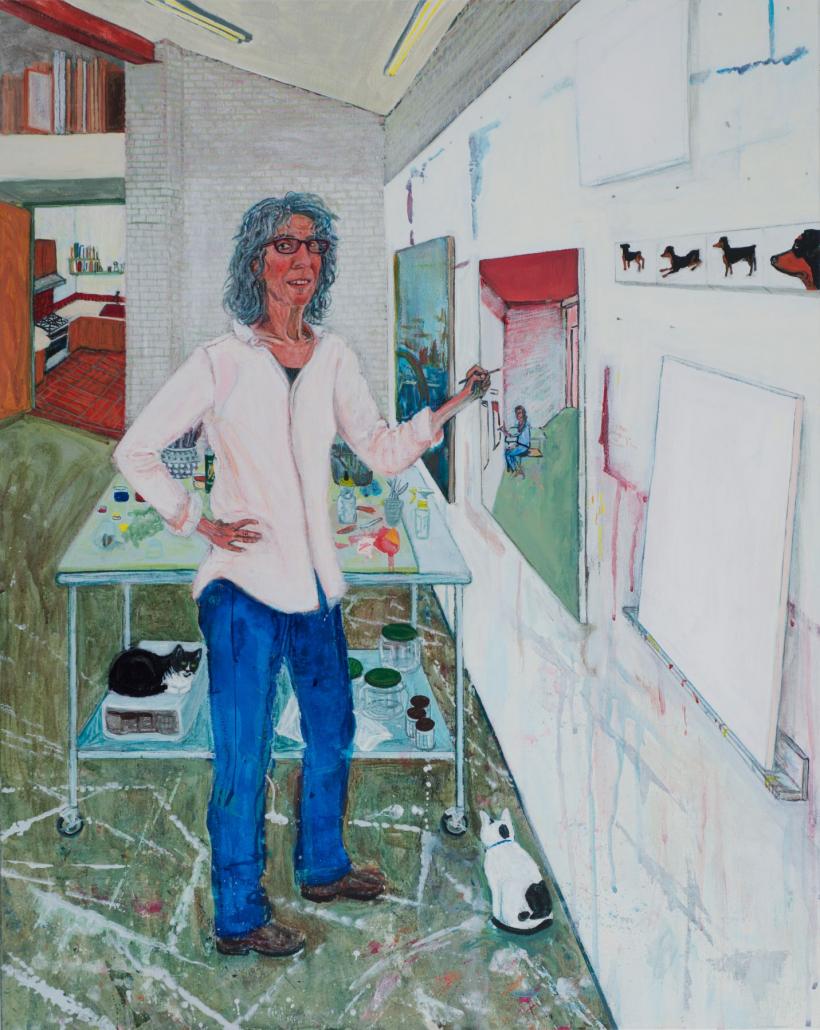

Yet the first clue that McEneaney’s paintings in ‘Callowhill’ are not as straightforward as they appear to be comes in viewing ‘Studio-Early 2019’ (2019), an airy, wide-look at her studio space. The perspective is deliberately skewed, allowing you to both look down at the surfaces of the paint-splattered floor and movable table while also looking up at the turquoise-blue ceiling. The spectator’s position is a place that does not physically exist; you seem to float just at the surface of the image, somewhat thrown off balance. And then you take a look at what McEneaney has captured in her depiction of her studio: nearly all of the other paintings on display in ‘Callowhill’ make an appearance in ‘Studio-Early 2019.’ Propped up on an easel, hanging on the wall, resting on the floor—the other works have been rendered in miniature and collaged onto the surface of ‘Studio-Early 2019,’ creating a delightfully playful and meta atmosphere that lingers for the rest of the show.

A pattern of sorts now established, every successive work in ‘Callowhill’ encourages a series of double-takes, inviting a challenge to find how many times a given painting has been reproduced as part of the decoration in another. ‘Enter Julius’ (2019) seems to re-stage the exact same composition as ‘Studio-Early 2019,’ with the exception of the inclusion of McEneaney herself, seated before a white canvas. It’s the first clue that McEneaney is not merely painting what she sees in her studio, but is creating her own slightly surreal reality: ‘Enter Julius’ features ‘Studio-Early 2019’ as the painting in the right middle ground mounted on the easel, while ‘Studio-Early 2019’ features ‘Enter Julius’ as the painting in exactly the same position in its own composition. McEneaney sits in the studio, painting an image of her surroundings in which the other works in the studio are themselves featured.

Presented almost as a diptych, ‘Cats SPS’ (2018) and ‘Pink SPS’ (2018) are never-ending, painting-within-a-painting, quasi-mirror images of one another. Staged more as self-portraits than as glimpses of her studio space, they are oddly reminiscent of surrealist self-portraits by Leonora Carrington, adding to their sense of the heightened uncanny. ‘Pink SPS’ depicts McEneaney standing, regarding the viewer while applying paint to a small image that is unmistakably ‘Cats SPS.’ In ‘Cats SPS,’ McEneaney is seated, applying paint to a miniature version of none other than ‘Cats SPS,’ while a tiny iteration of ‘Pink SPS’ hangs beside it. Both versions of McEneaney look at us knowingly, a hint of a smile on her lips, anticipating our reactions to her little game, knowing we’re wondering how far she’ll take it.

We step out of her studio into a cluster of works about the Rail Park, Philadelphia’s answer to New York’s High Line. A community activist as well as an artist, McEneaney has long advocated for the repurposing of the abandoned Reading Rail viaduct as an elevated public park that will span three miles over the city. The first chunk of Rail Park opened in 2018 in the Callowhill neighbourhood and in these works McEneaney imagines how the transformation will impact her life. In ‘Rail Park Winter’ (2019), she shows herself skiing along the snow-covered length of the park as perfect dots of snowdrift fall onto an enchantingly wintery city. In ‘From the Lasher-Callowhill Rail Park’ (2019), McEneaney envisions the park as an opportunity for respite and solitude in the bustling city. She paints herself and her dog on a walk in the park, the city completely empty but for the second version of McEneaney who sneaks into the composition on the far right, looking down upon herself from a tall building even as we look down at the entire scene.

‘Callowhill’ is a useful case study in the difference between transcription and art production. Transcription, the word that Locks Gallery uses to describe McEneaney’s paintings of her studio and of her life, is arguably more of a one-to-one transaction that documents everything that exists. What McEneaney is actually doing in these works, rather, separates art from transcription: she is purposefully constructing her own reality based upon her experiences as a working artist.