Rose Wylie’s paintings have previously been dismissed as ‘childish’. Her forms are decisive, irreverent, lucid; facial expressions are often reduced to a mere few brushstrokes. In this way, her paintings are, in fact, childhood remembered and rendered exactly as it exists for us as adults – as hazy fragments, as depictions not just of events or places, but of how it felt to be there. They teem with childlike wonder and energy, populated by an assorted cast of characters including dogs, ducks, footballers and film stars. And at 83, Wylie holds fast to the idea that our fleeting childish impressions never truly leave us.

So many of the paintings on view at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery allude to the park outside its walls: Wylie grew up in nearby Bayswater and her memories of walks through Hyde Park seem inseparable from the Blitz’s air raids. In ‘Park Dogs & Air Raid’ (2017), dark and clumsy war planes jostle up against one another in one scene, in much the same way as a group of dogs immediately below. Daubs of paint denote falling shrapnel overhead; the scene is pocked with cartoonish, fiery bangs – yet the scrapping dogs in the park show that life continued, more or less the same. The park as sanctuary to a world of characters is a setting that Wylie returns to often – with the park bench a recurring trope. She paints it as a place of intermission, for self-reflection, for migrants and the dispossessed to rest. It is also a site of memory, often inscribed with the names of the dead who liked to sit there while alive. At once literal and figurative, Wylie’s park bench, conjured from memory like most of her works, provides daily respite from urban life.

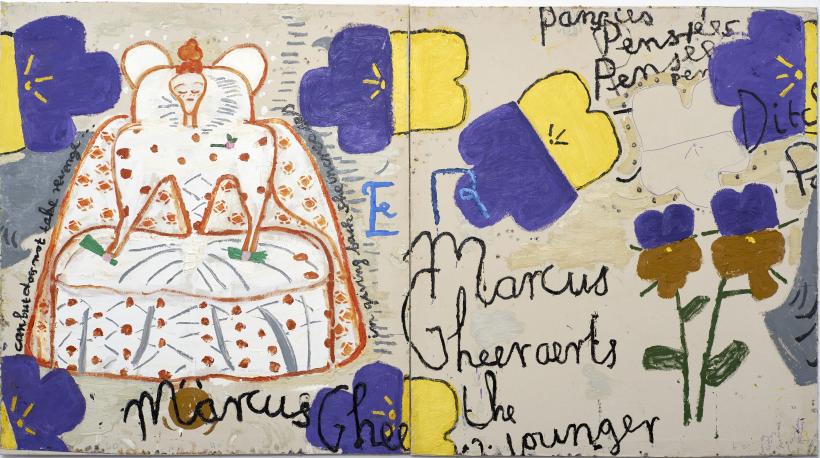

Many of Wylie’s painted scenes borrow heavily from cinema, revealing her particular filmic view of the world. Subjects such as Elizabeth I and Philip Seymour Hoffman look as at home in the artist’s eerie compositions as her own self-portrait. These works are often painted in homage to directors she admires, such as Quentin Tarantino, but also function as a way of using people who have already become objects or images through the constant slew of media. Wylie takes these near-daily encounters with, for example, Elizabeth Taylor’s swimsuited body, and then exaggerates those curves, dismembers her at the torso between two canvases, and surrounds her with an unnerving pattern of unblinking eyes and ears. Provisional and rough, Wylie’s compositions are also deliberate, using various kinds of precise cinematic framing, cutting between long and close-up shots. Text rolls across the canvas – often like credits, title sequences or magazine covers – but at other times lifted directly from the diaries Wylie draws in initially. Writing, as with children, is just another form of mark-making here. Her tendency towards cinema demonstrates all the childlike elements of rudimentary imagination, but also underlines the care Wylie applies to painting. Memories are delicate objects, to be teased out gradually and framed on the canvas as they exist in our minds, with all manner of seemingly random words attached to them. If Wylie’s paintings are childish, it is in their straightforward, unbridled connection to place and character – and their firm anchoring in the artist’s mind.