In the blistering heat of August, I found myself walking down the bank of the Rio Teju to the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology in Lisbon. The news that week had been filled with images of environmental destruction: the beach resorts of the Algarve were covered in fire; planes dropped water on charred forests in California; the urban infrastructure of New Delhi melted into pools of tarmac. Images of burnt landscapes from a Cormac McCarthy novel repeated endlessly. And the word on everyone’s lips: the Anthropocene.

For the past few days Lisbon had been advised to stay indoors. My dry eyes itched and, like many others, I was tired from lack of sleep. If, as journalist and activist Naomi Klein remarked, climate change faces a communication problem, then the over-heated body makes us feel what we need to articulate. This is the challenge the Anthropocene poses us. Coined to describe the new geological epoch as one in which humanity has left a lasting impact on the planet, the Anthropocene has been the subject of numerous exhibitions and projects. But as each year brings a seasonal cycle of media-spectacle followed by forgetting, what new forms of knowledge are needed to shift our relation to the planet?

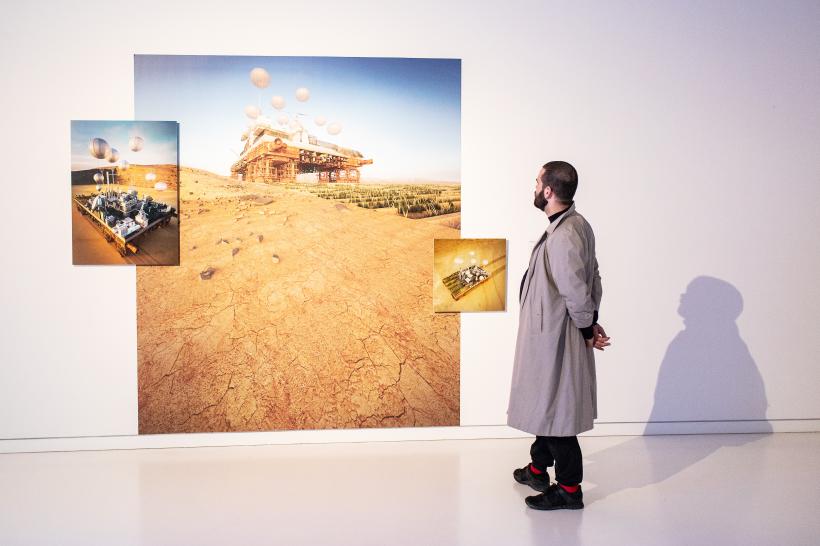

Eco-Visionaries: Art, Architecture and New Media After the Anthropocene is the museum’s provocative answer to that question. Curated by Mariana Pestana and MAAT Director Pedro Gadhano, the show brings together an array of different practices that seek to respond to the current geological epoch. If climate scientists continue to debate when the Anthropocene began, this exhibition begins by accepting it as an urgent planetary and socio-political reality. There are no escape plans to Mars or deferrals to artificially intelligent deities here, but instead a series of propositions that seek to understand, re-imagine, solve and critique humanity’s exploitation of the planet.

The exhibition is organised around five clusters including ‘Adaptation’, ‘Co-Existence’ and ‘Extinction’ that span pragmatic solutions to dystopian warnings. In the first gallery, John Gerrard’s (2017) Western Flag is juxtaposed with Territorial Agency’s Museum of Oil (2016). The former is a short and meticulously computer-generated image of a flag of sprayed oil, wittily subverting the USA’s Stars and Stripes. Just as this work reveals the hidden power of the oil industry in creating the hegemony of the West, Territorial Agency’s project brings together information and artefacts to challenge oil-extraction across the globe. Both works, in differing ways, adopt the strategies of visual culture to re-think our relationship to nature’s finite materials, setting up the multi-disciplinary attitude that spans the exhibition.

Speculative and critical design feature throughout in the work of Dunne & Raby, MVRDV, Parsons & Charlesworth and others. Across this cluster of works is a shared interest in engaging with scientific and technological research, expanding its possibilities whilst creating spaces for critique. In her work Designing for the Sixth Extinction (2013-2015), Alexandra Daisy Ginsburg proposes that bio-design may be an effective response to mass species extinction. A series of diagrams for fictional organisms show creatures that would collectively adopt the roles of extinct species, for example an Autonomous Seed Dispenser which is genetically designed to spread seeds from local plants. The proposition of the work is that these would collectively adopt the roles of extinct species to create a sustainable eco-system. Ginsberg’s new organisms are propositions at the limits of the plausible, leading the viewer to ask, in the tradition of speculative design, whether a future in which these designs are needed is desirable.

More immediately pragmatic approaches to the Anthropocene also feature. Bjarke Ingel’s Amager Resource Centre (2013), a mountain-like waste energy plant in Copenhagen, is shown through a series of images. Next to it is a small, almost human sized, bio-gas power generator designed by Portugese architects Skrei. Both, unlike the speculative propositions, are concrete design-solutions. The Amager Resource Centre was completed in 2017 and is one of Copenhagen’s major steps to becoming the first carbon neutral city. However, placed within the context of the show, these too take on a speculative character, asking us to reflect on the planetary implications of such adaptations.

As Mariana Pestana notes in her catalogue essay, humanity’s impact on the planet began to rapidly increase at the same time as 18th century Europe adopted (and elevated) scientific rationality as a system for understanding and exploiting the natural world. One of the exhibitions merits is the inclusion of a range of projects that seek to decolonize environmental activism and its modes of understanding. Carolina Caycedo’s (2017) Serpent River Book, for example, charts the consequences of privatizing and building damns on rivers for the indigenous populations that depend on them. Refusing to adopt one ‘gods-eye’ view, this accordion fold-out book brings together photography, myth, drawing and written text to map-out the effects of river privatization.

Post-colonial critique and rivers also feature in Ursula Biemann and Paula Taveres Forest Law (2014), a film which centers around a series of legal cases in Ecuador that led to the state granting legal rights to forests of the Amazon. Testimony from indigenous leaders and activists involved in the battle reveals the challenge of working against a legal system that does not acknowledge other ethical codes toward the natural world. As one leader mentions, the courts “didn’t understand the sacred”, and by extension failed to recognize the ethical relations that indigenous peoples held to the forest. It is one of the most powerful works in the exhibition, a reminder that solidarity in the environmental struggle will need to operate not only amongst different peoples, but likely also between epistemologies.

Walking through the exhibition, I thought of a story that appeared in the guide-books I’d read about Lisbon. On a Sunday morning in 1755 the city began to shudder, startling its inhabitants as buildings started to collapse. Thousands interrupted their morning prayer fearing divine retribution, emptying the churches only to be killed by a tsunami minutes later. The great Lisbon earthquake brought the end of Portugal’s colonial supremacy and became synonymous for Enlightenment thinkers with the problem of Evil: how could God, a benevolent and all-powerful being, allow terrible things like this to happen on Earth?

Today, many would have described the earth-quake as a natural disaster. But as the art-historian T.J. Demos has argued in Decolonizing Nature, climate change is always already a socio-political problem, one moreover that has differing consequences depending on geographical location, wealth and the form of life of those affected. Would so many in Lisbon have died if there had been no buildings, or even if their Sunday morning had been spent inland? Forest Law powerfully stages the complex intersection of geography, culture and history by locating the testimonies within the Ecuadorian Amazon itself, positioning the narrative both subjectively and geographically. Eco-Visionaries also achieves an exceptional piece of positioning, not only in the heart of a city marked by environmental change, but one that places the urgency of ecological activism at the heart of art, design and the civic debate.