‘dark frame / deep field’ at London’s Breese Little sets out to examine the shifting role of aesthetics in communicating our knowledge of science, space and the universe. The show takes its inspiration from the photographs that NASA used in the 1960s to relay and dramatise the progress and excitement of the space race. The curators, Marek Kukula and Melanie Vandenbrouck, have used these iconic images as a foil to explore the role that artists may play in translating this information today.

On first view the show appears as a great panorama of greys, this is largely due to a prominent nine page drawing entitled ‘Crater’ (2013) by Caroline Corbasson which adorns a complete wall in the small gallery. The piece drifts in its charcoal tonality from the deepest black to the unbleached cream of the natural paper. It depicts a crater, referencing Galileo’s drawings of the moon but in reality being simply a study of an Arizona landscape. This is paired with another work, ‘Naked Eye’ (2014), a rendering of numerous layers of star maps, creating a strong visual realisation like an incomprehensible piece of scientific information. This brings into sharp relief one of the key concerns of the exhibition - science and technology, or more precisely the shifting nature of our idea of space depending on the aesthetic potential of the technology used to display it. It is a complex question with no clear answers, and is more than a little complicated by the greater geopolitical value of the material produced.

In the context of the recurring reference to NASA, it is the idea of adventure that is most overtly felt and nowhere in the exhibition is this more powerfully displayed than in the immense black and white photograph entitled ‘Blackout 13’ (2010) by Dan Holdsworth. In this image the artist turns an enormous Icelandic landscape into something dark and alien: a sort of bleak dystopian future. More importantly its colours are reversed, rendering its blacks white and its whites black, making the landscape something of a fake, or at the very least a misrepresentation. The notion of authenticity is a crucial question that hovers inconsistently over the show. It is also touched upon by the artist duo We Colonised The Moon who present a false lunar artefact in ‘As Good As A Moonrock’ (2012).

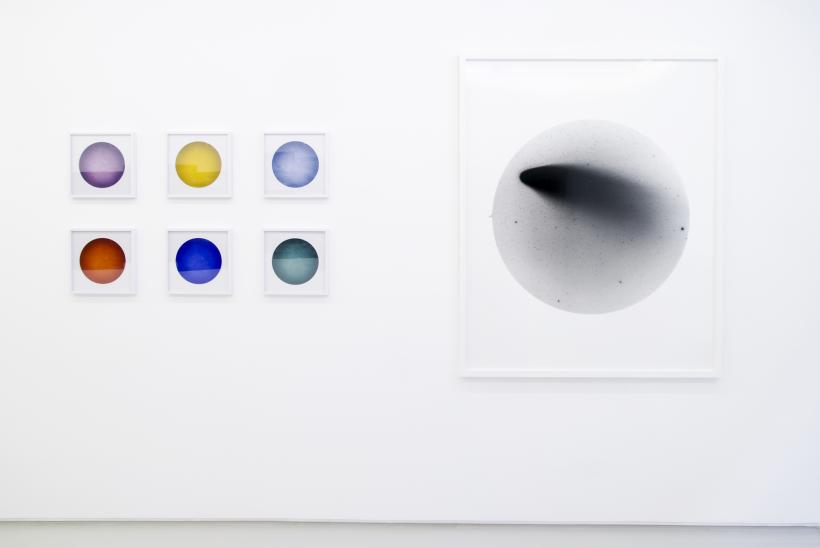

The rest of the exhibition focuses predominately on the distinction between the analogue and the digital, from Sophy Rickett’s presentation of technologically obsolete astrological photography, to Philippe Pleasants’ digital c-types which use slow exposures to trace the movement of the sun and moon across the sky.

Alongside all of these new works is a wall of the real thing: the archive photographs from NASA. They are a highly aesthetic view of a moment in time and technology, infinitely fascinating in their construction. These images are tough competition for the artists who hang next to them, but then that is surely the point. If, as the press release says, it is ‘artists who are best equipped to interpret what these dispatches tell us about humanity’s relationship to the cosmos’ then they better get used to the competition.