“I want to alert Donald Trump that there is other scary stuff on the internet, too”, said chat-show host Stephen Colbert back in March 2016. Trump, then only a seemingly-harmless candidate for Republican presidential nominee, had just been fooled by a doctored YouTube video which appeared to link an anti-Trump protester to ISIS. He duly re-tweeted the video, taking it at face-value. When confronted about it on NBC, he uttered his now-famous response, which gives this exhibition its title: “What do I know about it? All I know is what’s on the internet.”

To this exhibition’s immense credit, it avoids engaging in knee-jerk satire of the American President (which sometimes proves toothless and often has the opposite of its intended effect - just ask Jimmy Fallon, whose jocular interview with ‘The Donald’ appeared to humanise him to voters and boost his campaign). Instead, his words serve as a jumping-off point to consider the blurrier than ever line between fact and fiction, and the changing nature of ‘the image’.

Perhaps it’s hardly news that Trump is so ridiculous as to be almost irony-proof, but ‘All I know is What’s On the Internet’ displays a more impressive maturity in that it also avoids the pitfall of performed ‘wokeness’ or trope-ish tech-phobia of the sort mocked in meme groups like “What if phones, but too much?” Colbert is right: there’s scary stuff on the internet. But far too much art made in response ends up seeming sophomoric, “Red Pill”, preachy (see Steve Cutts’ animated music video for Moby’s 2016 track, ‘Are You Lonely In This World Like Me?’).

Instead, here at The Photographers’ Gallery, we have incisive diagnostics at work, exploring the new global image economy in all its uncanny vastness but also its potential for communication and political resistance. Winnie Soon’s ‘Unerasable Images’ (2018), for example, tracks the persistence of a certain image appearing in Google searches - a reproduction of the famous Tiananmen Square ‘Tank Man’ photograph made from Lego. Because it’s made from toy bricks, it dodges China’s censorship of the iconic picture in a way that’s cartoonish and silly but also moving.

The ‘scary stuff’ of the internet is also viewed from a refreshingly oblique vantage. Evo and Franco Mattes’ ‘Dark Content’ presents a series of interviews with content moderators who view the darkest matter out there and remove ‘offensive material’. Computer-generated avatars speak in place of the interviewees to protect their anonymity. The monotones give a weird power to moderators confessing to censoring homosexuality for ‘the Mormon internet’ or expressing pride in their protective role.

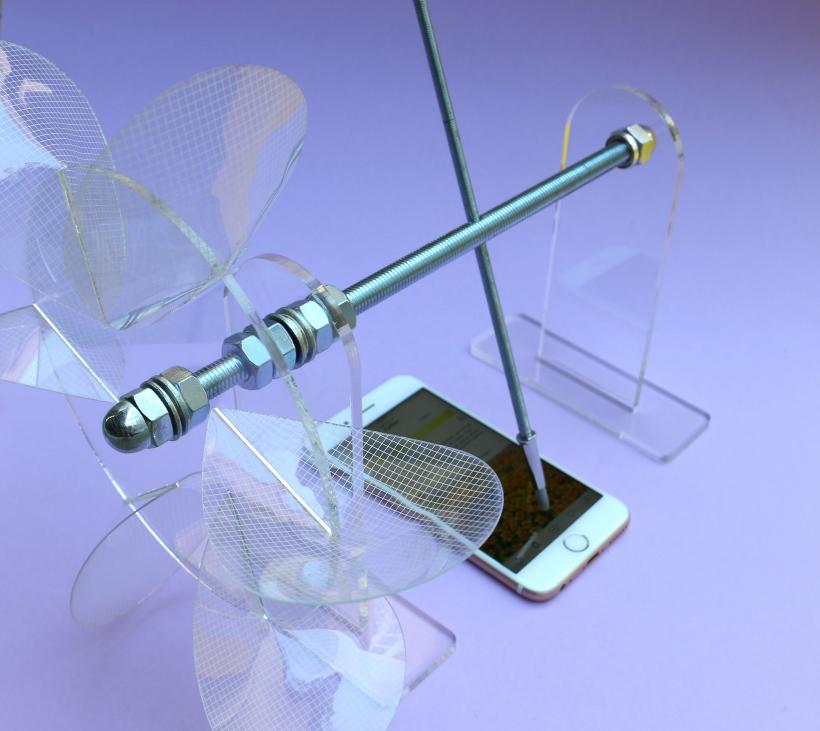

Chillingly, the entire back wall of the one-room show is given over to Mari Bastashevski’s collation of surveillance data collected by various companies, including microphone taps and metadata harvesting. Andrew Norman Wilson’s series showing Google employees’ hands which have accidentally scanned into digitised books provides levity but also a piquant broaching of the human-machine divide. Italian collective IOCESE prove just how easy it is to start an international conspiracy theory, whilst Schmeig and Lorusso battle the sheer impossibility of cataloguing internet imagery by printing out five years of ‘Captcha’ tests (those ones where you prove you’re not a robot).

The overall experience of this exhibition reminds me of one of the best videos on YouTube, entitled, ‘Barry Benson saying “ya like jazz?” 1,073,741,824 times’. It’s exactly what it sounds like, the animated honey bee from the 2007 ‘Bee Movie’, voiced by Jerry Seinfeld, delivering his most infamous line repeatedly, layered over himself more each time. By the time Seinfeld’s overlaid voice reaches the billion mark, it sounds like a sort of digital brushstroke, an ambient daub of data. It’s unsettling, it’s illustrative, and it’s kind of beautiful. So is this show.

The exhibition attempts to redefine the act of looking at images in response to the ever-changing way in which images are produced. It’s a Sisyphean task but by gesturing towards its near-impossibility, the exhibition goes a long way to achieving it. When trying to look at something that’s self-replicating, regeneratively fractal and reduplicative, you need to look as through a kaleidoscope. Or sort of ‘squint’ like looking into a great distance. I’m not sure but I’m trying to keep up. What do I know about it? All I know is what’s in ‘All I Know Is What’s On the Internet’. Luckily, that’s a very good start.