There’s a pleasing synchronicity to current Edinburgh exhibitions, which together trace several paths to abstraction in artistic production during the latter part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. The Ingleby’s current exhibition ‘ABJAD’, featuring work by Jane Bustin, Kevin Harman, Paul Keir and Jeff McMillan overlaps with a show of abstract paintings by the Belgian artist Raoul De Keyser at Inverlieth House, and with the Fruitmarket Gallery’s ‘Possibilities of the Object: Experiments in Modern and Contemporary Brazilian Art’, which features sculptures teetering between everyday materials and abstract meditations. A similar tension inflects works by the artists included in ‘ABJAD’, who each delight in exploring the valence of different media while continuing to push the medium-specificity of abstract painting.

This is particularly apparent in the work of Jane Bustin, whose works constitute one of the most elegant sections of the Ingleby show. Bustin combines acrylic paint with more unconventional materials like paper, linen, porcelain and copper, layering them over small rectangular sections of wood that slot together to create idiosyncratically shaped supports. Bustin’s incorporation of paper is particularly intriguing: ‘Tablet II’ and ‘Tablet IV’ (both 2014) feature torn-out pages from blank notebooks, already yellowing slightly. In each, the paper has been smoothed and flattened to the extent that it evokes both polished stone and the sheen of an e-reader screen, resulting in a subtle play on changing forms of recording and memory.

Equally, in ‘Christina the Astonishing VI’ (2014), which as its title acknowledges is Bustin’s star piece, the use of polished copper to create a mirror-like surface in which the viewer catches their own surprised reflection underlines the use of materials to explore audience perception and response. This work in particular sees Bustin channelling minimalism’s interest in phenomenological experience: Bustin has coated different sides of the wooden support in neon orange, pink and blue, so that the surrounding wall becomes infused with colour, reminiscent of Dan Flavin’s sculptural experimentation with fluorescent lighting.

Bustin’s work finds its closest correlative in several small wooden pieces by Paul Keir, which alternate between letting the plywood base soak up watered-down gesso, and the heavy application of thick globules that float on the surface. At the other end of the scale, Kevin Harman’s large works encase marbled slabs of congealed household paint inside heavy steel frames and double-glazing units, which lie suspended under aquarium-like glass, sealed off like some undefined geological sample. In two works hung side-by-side and entitled ‘6am’ and ‘Through in and out’ (both 2014), horizontal veins of colour – one nauseous pink and yellow, the other aqua rimmed with blood-red – evoke streams of condensation and unhealthy green-house growths.

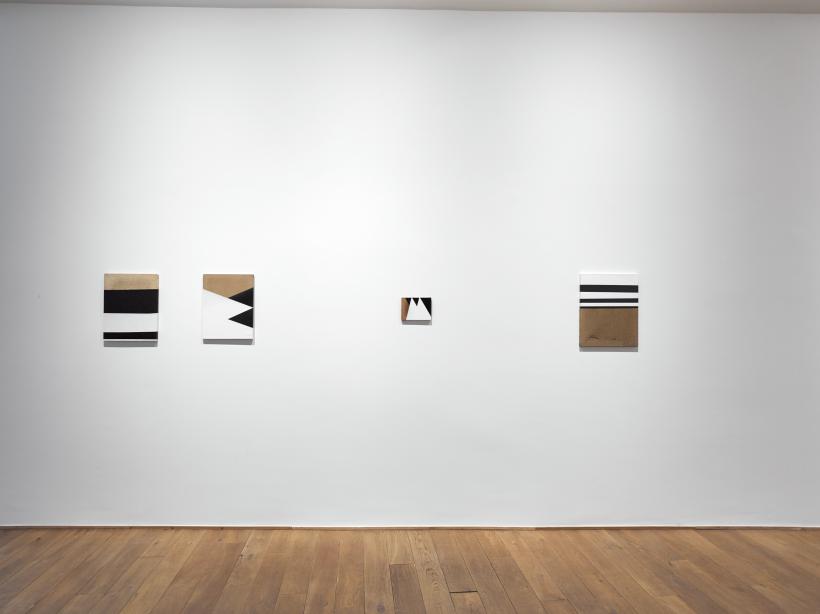

The possibilities of abstraction offered by everyday materials continue to be explored in Jeff McMillan’s ‘Offside Paintings’ (2013-14), where wood and metal gloss paint have been layered onto sections of rough linen so thickly that in some places it acquires the texture of an enamelled shell or protective carapace. Also included in the show are two of McMillan’s ‘Demonstration Paintings’ (both 2013). McMillian’s biography contextualises these by relating how in 2013 the artist was asked to participate in the Art Party Conference at Scarborough. Rather than making a banner or slogan, McMillan created a painting to ‘represent abstraction’, which he affixed to a pole for marching with instead. Although traditionally hung at the Ingleby, the ‘Demonstration Paintings’ hint at both a perceived need to defend abstraction, and to the multiple sites of abstract art throughout the twentieth century currently being explored by shows such as the Whitechapel Art Gallery’s ‘Adventures of the Black Square’.

The desire to ‘represent’ abstraction, and even to endow it with a ‘protective’ quality, to uphold it against its detractors and promote its adaptive, unceasingly inventive potential, is a latent but generative implication of ‘ABJAD’. It is significant that, for artists like Harman, abstract painting is part of a wider practice that includes performance, and that for all of the artists here it involves an openness to diverse media and installation. This is underscored by Keir’s ‘Untitled’ (2015), a wall painting whose delicate purple lines proliferate across the upper floor of the Ingleby Gallery, and his ‘Untitled’ (2011), which consists of playful ink drawings on 40 leaves of salvaged paper. It would have been fascinating to have these interdisciplinary and intermedia qualities bought out even more within ‘ABJAD’, but there’s still a strong sense that each of the works on display could be seen as a ‘demonstration painting’ showcasing abstraction’s diverse capabilities.